Generating knowledge about RA

Regenerative Agriculture (RA) is presently a topic of discussion world-wide. RA itself is not a specific, defined system, but incorporates several components which aim to improve soil quality and increase soil carbon.

Most of these are already well-established in NZ farm systems, i.e. using pasture, rotational grazing, minimum-till cultivation, and minimising bare soil with cover crops.

Here we look at two key themes of RA in a NZ context.

Organic matter & soil carbon

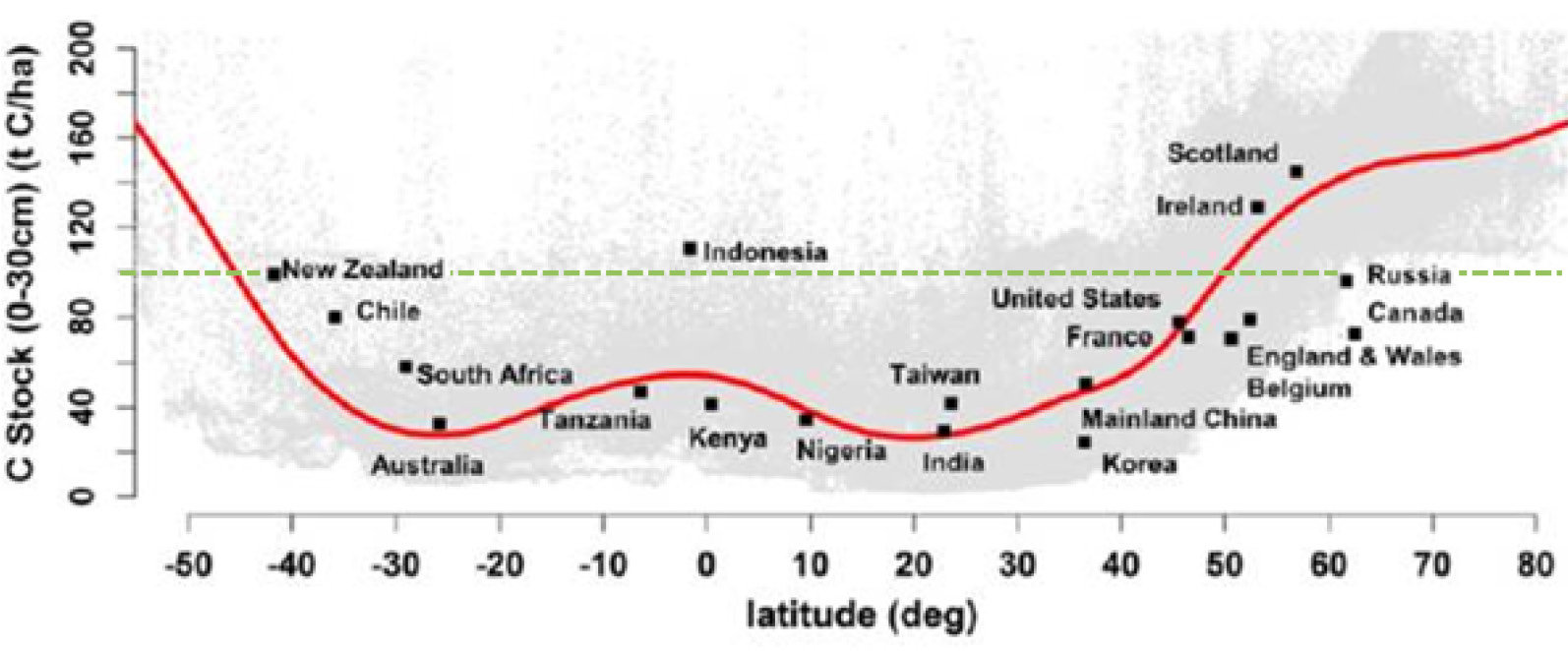

Scientists estimate NZ soils contain 99 t/ha soil organic carbon (SOC). This is higher than many other countries, such as areas of North America, South Africa and Australia. There are several reasons for this, including our latitude and cooler climate.

Global soil organic carbon by latitude (Minasny et al. 2017)

NZ agricultural soils are dominated by permanent pasture, rotationally grazed by sheep, cattle, and deer. This is not the case in many other countries.

Some overseas farmland has been historically heavily cultivated and cropped, which inevitably depletes soil organic matter.

It is primarily in these ‘degenerated’ carbon-poor soils that RA practices have been associated with ‘regenerating’.

For example an increase of SOC of 4t/ha/year was estimated in Michigan, USA, to 50t SOC, through changing from set stocking to rotational grazing (Stanley et al. 2018); or an increase of SOC of 8t/ha/year was estimated in Georgia, USA, to 40t SOC, through conversion from cropping to sowing pasture and rotational grazing (Machmuller et al. 2015).

In Lincoln, NZ, an increase of SOC of 5t/ha/year was estimated, to 77t SOC, through sowing a degraded cropping soil into pasture (Francis et al. 1999).

In this trial the same increase in SOC came from sowing a pasture of straight perennial ryegrass, versus a pasture mix of prairie grass, timothy, tall fescue, chicory, lucerne, white clover and red clover.

Diverse seed mixes for pasture

While most of RA focuses on the use of pasture, min-till establishment and rotational grazing, some proponents suggest sowing diverse seed mixes.

For pastoral-based soils in NZ which are typically rotationally grazed and high in SOC, there is presently no scientific evidence that sowing a very diverse pasture seed mix will increase soil carbon.

Another suggestion in RA is to use a longer grazing rotation, letting plants lose feed quality and rot down into the soil.

However, a standard grazing system can grow a similar amount, returning the plant nutrients to the soil through dung and urine (rather than as plant material).

And under good grazing pasture quality is higher, leading to better animal performance.

Ryegrass and white clover are the two most widely sown permanent pasture species in NZ grazing systems because:

- Decades of scientific research in NZ have shown ryegrass is a highly efficient photosynthesiser across most of the country. Its growth habit, productivity, and grazing tolerance allow it to thrive in a diverse range of climatic conditions and livestock systems.

- Likewise research has repeatedly demonstrated white clover adds significant value to our grazed systems, improving animal nutrition and overall pasture DM growth and capturing atmospheric nitrogen.

Even so, successfully managing these two different species in one grazing sward over several years is not always easy, because each has different requirements for establishment and survival.

Many other plant species have found a place in NZ farm systems, including cocksfoot, meadow fescue, brome and prairie grass, timothy, phalaris, lucerne, red clover, lotus, annual clover, chicory and plantain.

Within the ryegrass family, development of tetraploid and hybrid ryegrasses, as well as on-going advancements in novel endophytes, have further broadened pasture diversity.

In effect NZ has been researching and practicing multi-species pasture mixes for many decades and has built a great deal of practical knowledge about what species grow together, and how.

But as we see with white clover in many NZ ryegrass pastures, a simple, widely used, two-species mix is in fact a highly complex relationship requiring careful management to maintain both productivity and sustainability.

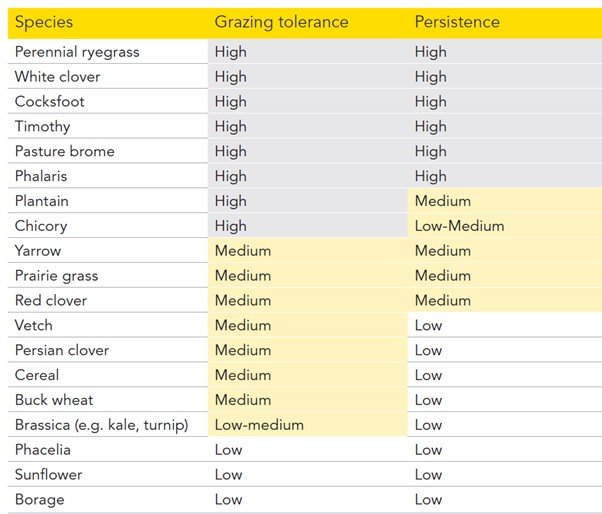

Every time another species is added to the pasture mix the level of complexity increases, and may need very different (and in many cases incompatible) management as the grazing tolerance and persistence of species varies hugely.

It’s been suggested that adding fast establishing species to a seed mix can be a ‘cover crop’, protecting slower establishing species.

This concept has commonly been used on sandy soils, prone to wind erosion to provide quick ground cover.

However, in most situations results of this practice are mixed, as the fast establishing species compete for light, nutrients and water with slower establishing species, so can suppress their establishment.

Also if the fast establishing species don’t persist, bare soil left in their wake encourages weed infestation.

Conclusion

The philosophy behind RA to farm with a focus on soil health and soil carbon is a good one. It is also the aim of much of our NZ pastoral system, driven through pasture use, rotational grazing, and where applicable minimum tillage and cover crops.

The science has shown you cannot effectively combine 10, let alone 30, diverse plant species in a grazed pasture. Over time the grazing tolerant and persistent species dominate.